Understanding the Reconciliation Process

Congress is expected to pass one or two reconciliation bills in 2025. This guide will teach you to understand the budget reconciliation process.

From background to details about process and procedure, what to expect, and more, this article has everything you need to know to gain a comprehensive understanding.

Background

The Congressional Budget Act of 1974 outlined the budget reconciliation process which allows Congress to expedite legislation regarding (1) spending, (2) revenues, and/or (3) the debt limit. Senators are allowed to block provisions of a reconciliation bill that do not strictly address one of the three aforementioned aspects of the federal budget, limiting the scope of the legislation.

Reconciliation is a unique mechanism used in Congress, as it is not subject to the filibuster in the Senate chamber. This means that the bill does not need to pass the 60-vote threshold, like most legislation in the Senate, and can pass with a simple majority. Currently, with a 53-47 majority in the Senate, Republicans have the power to pass this legislation in their chamber without Democratic support.

Process and Procedure

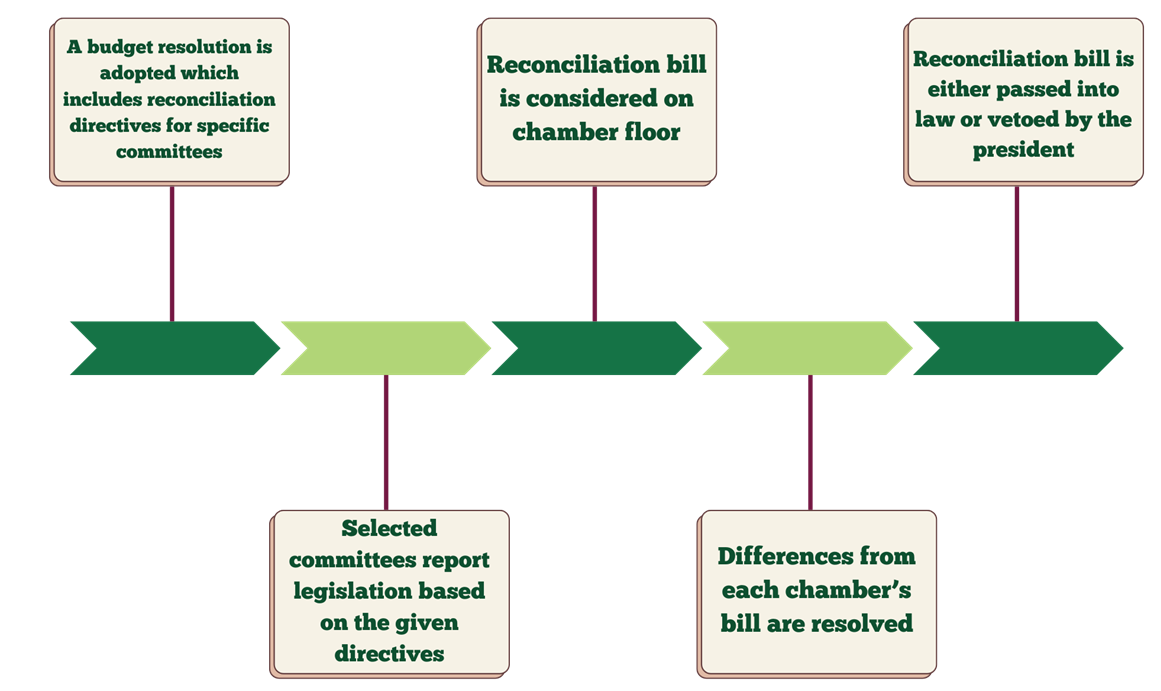

The budget reconciliation process begins with each chamber adopting a budget resolution and laying out their plans for spending and revenue. The House and the Senate must then decide if they want to include reconciliation directives into the budget resolution. If included, the budget reconciliation process will begin. These directives assign selected committees to create legislation that either: (1) increases or decreases spending; (2) increases or decreases revenue; or (3) changes the debt limit. If multiple committees are given directives, they must submit their legislation to the budget committee in their chamber, which will then combine all legislation into one bill. If only a single committee is given directives, their legislation bypasses this step, immediately going to a vote on the respective chamber’s floor.

Amendments to the bills can be offered, with one caveat: they must not increase government spending. If the House and Senate pass different versions of the reconciliation bill, they must confer to settle any differences. The finalized bill is then voted on by each chamber, needing a majority of each to pass. If the bill passes both the House and Senate, it is sent to the President’s desk, who can either sign the bill into law or veto it altogether.

What to Expect

While Republican leadership has yet to decide if they will work on one, large reconciliation bill or two, smaller ones, we can expect to see some form of reconciliation legislation this year that tackles major political issues such as immigration and the border, energy, and extending the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017. Because there is no filibuster allowed in the Senate for reconciliation bills, Republicans will try to include as much of their platform as possible into the bill(s), as they do not have a supermajority to end a filibuster. Other topics, such as healthcare or food assistance, may very well be included. Republicans aim to begin work on this legislation as soon as possible.

Particularly relevant to ACT and the transportation industry is the extension of the TCJA. Because it is set to expire by the end of 2025, Congress must pass legislation if they want to extend it. With our new recommendations for commuter tax benefits, ACT sees this as a legislative opportunity to advocate for our proposed recommendations through a reimagining of the qualified transportation fringe benefit previously included in the legislation. To learn more about ACT’s recommendations for commuter tax benefits, please register for our webinar below